Maestro Arkles

For the past two weeks, I’ve spent from 1-4pm, Mon-Fri, at the studio of Jason Arkles (Studio della Statua), learning human figure clay modeling. Yesterday evening, after the last session, Maestro Arkles sat down with me and told me the story of how he went from being a college theatre major to Florentine sculptor – in only 25 years. (his life – not the time it took to tell the story).

We’ll start after college. Young Jason was a theater major, and after a couple of years of college, moved to North Carolina to join a cooperative theater company where the members had the opportunity to write and produce their own works. Jason was a puppeteer and learned a lot of sculpture-related skills in the theater company – construction, mold making, etc. He got so good at making puppets, in fact, that a friend recommended that he apply for a spot at a famous and very exclusive French puppeteering school. So, Jason spent a year studying French and developing a portfolio and then shipped off to France for an audition.

There are many points of serendipity in this story. Here’s the first one: While on the plane to France young (and broke) Jason meets a flight attendant who tells him about a bookstore in Paris called Shakespeare and Company. The bookstore is a bit of a cultural Mecca, and the proprietor sometimes allows interesting young people to sleep above the shop in exchange for a bit of help in the store. So, Jason finds this store, is accommodated, and while there, meets a Scottish girl with a bang-up street performing routine. He goes and auditions for the puppeteering school but doesn’t make the cut. So, the Scottish girl says, “Hey, why don’t you join the street-performing circus I’m putting together and travel Europe with us?” Jason says, “Why not?” and throws away his return ticket to the US.

He travels around Europe for awhile with this group, putting on puppet performances and living off a few coins per day. It’s miserable, and he hates it. Eventually, the group finds its way to Florence where, because of the connections of one of the group members, they have hopes of sleeping indoors, eating, and maybe taking a shower.

The place where Jason ends up sleeping the first few nights in Florence is at the Charles Cecil School which is a well-known painting atelier. If I have my history right, Charles Cecil and Daniel Graves (founder of the Florence Academy) are the two Americans who are largely responsible for the realist painting renaissance that has been going on in Florence since the 1990’s. Jason showed up in Florence and was sleeping on Charles Cecil’s studio floor in the mid nineties.

By this time, Jason is done with the itinerant puppeteer life. He decides to stay in Florence and finds work modeling for the drawing and painting classes at the Charles Cecil School. While he is working there, Cecil decides to start an experimental sculpture department. This is the second serendipitous occurrence, as I see it.

A little digression about Cecil, Graves, and realist art-making. There’s this thing called sight-size. It’s the method that both Cecil and Graves use for teaching drawing. It basically means that the model and the drawing appear at the same size as each other from the observation point of the artist. It’s a practical, effective way of learning to draw and has a bunch of historical precedent. At this point, in the the 90’s, there were drawing and painting programs that used the sight-size method, but *no* sculpture programs that did. Cecil had reason to believe that, historically, sight size had been used to train sculptors and he wanted to revive the method. So, this experimental sculpture program was actually really important as far as the realist art atelier movement went.

Jason had only been involved at the Charles Cecil school for a six months or so, and he wasn’t even an official student (although, it sounds like by this point he had become interested in what the students were doing and was learning by watching and listening). But, he did have considerable experience, from his puppet-making days, with the technical side of making 3-D objects. When the experimental sculpture department started, Cecil hired Jason to be the assistant to the artist heading up the program, a guy named Sam. And, as part of the deal, Jason got to participate in the drawing program at the school for free. Since he now is in a position where he is giving instruction to students who have more official training than him, Jason works *really, really* hard, learning as much as he can and doing the best job he possibly can so that he can keep his position and the respect of the students. After awhile, Sam leaves the school, and Jason takes over his position as head of the sculpture program.

While heading the sculpture program, he also takes a couple of month to go to Pietrasanta and squat in one of the marble laboratorio there. The studio lets him hang around and learn everything he can from the other carvers. So, now he’s got some drawing training, sight-size sculpture experience, and marble-carving skills. Jason told me that, when he was growing up, he didn’t even know that people still made sculptures like the ones you’d see in museums, but he’d go to a museum and see a figure in stone and say, “I want to make *that*.”

Now, Maestro Arkles is making sculptures – human figure studies and portrait busts. (The Charles Cecil School is, in fact, ultimately a school of portraiture.) Jason decides that now he’s ready to go off and be an artist on his own. Plus, it’s difficult to stay in Italy long-term legally. So, he moves back to the US, to North Carolina. For several years, he works construction as his day-job, travels back to Italy periodically (partly by way of working for a bike-touring company) in order to help out in the Charles Cecil Sculpture Dept, and works on his own sculptures.

As far as his work goes, he’s making commissions and entering competitions. True to his background in theater, his work typically has an element of narrative. Sculpture is basically another form of storytelling.

The back and forth lifestyle was not sustainable, however. After about 10 years of living this way, he realized that it wasn’t working, and he needed to pick a place to stay. He chose Florence, and (I’m a bit unclear about this part) it sounds like it was a bit of a risk to pick up and leave North Carolina. He had some work teaching privately in Florence, but at this point was not making a living off of commissions and couldn’t legally get paid for work in Italy. At the same time, the Charles Cecil Sculpture program closed. One of Jason’s former students and Charles Cecil, Raffaelle Romanelli also happened to own the sculpture studio space rented to Charles Cecil. Raffaelle decided to open his own studio and, quite reasonably, took the studio space back.

So, Jason was in Florence full-time now and on his own. One Sunday morning, he wakes up, groggy and wishing he hadn’t gone to the pub with art students ten years younger than him the night before. He thinks to himself that he’s got to do something with his life. Now for the 3rd instance of serendipity: Jason has noticed an empty niche on the facade of St. Mark’s English Church (where he knows a few people) near the Ponte Vecchio. St. Marks is in the middle of doing some property improvements, and Jason thinks that maybe this means they have the budget for some sculpture. So, he grabs his portfolio and shows up at the end of the coffee and donuts (not sure if they do donuts in Florence, but you get the idea) and approaches one of the chaplains. He says to the chaplain, “You need a St. Mark statue for your empty niche, and I can make it for you.” The chaplain, amazingly, says, “You’re right, and you’re the person for the job.” Jason charges them a bargain rate and makes the sculpture for the niche, becoming the only American, living or dead, to have a figure sculpture publicly display in the city-scape of Florence.

This commission and the fact of being “the only American with a sculpture in the city-scape of Florence” becomes his claim to fame. People start calling him. After the St. Mark, three large commissions in the US come in. This gives him a little money and breathing room. He rents his first studio Florence and continues to receive commissions – portraits, sacred art, funeral monuments, copies of old masters, both in Italy and abroad.

At the same time, he also is continuing to teach and to reflect on the sight-size method of sculpture that was the foundation for the Cecil sculpture department. He translated an out-of-print book written in French on Francois Rude, a sculptor working in the early 1800’s, who worked and trained other sculptors using the sight-size method. And, Jason began writing a book explaining the method used by Rude. As part of this writing process, he studies art history more broadly and gave a lecture series through St. Marks which was well received. This led to a position lecturing at the British Institute in Florence and to the production of his now-famous podcast The Sculptor’s Funeral. As Jason says, “It’s easy to be the best in the world when you’re the only one.” No one was doing a serious podcast on the history of sculpture. So, Jason started one.

A few years ago, Jason moved into his current studio in the basement of the Palazzo Capponi in the historic center of Florence. The same family has owned the Palazzo for the last 600 years and continues to support the arts – now, in part, by renting the studio to Jason. This is the studio in which I have spent the past two weeks for my workshop. It’s a labyrinth of rooms with vaulted ceilings and feels like a cross between a dungeon and a wine cellar.

Here, Jason does all his work, from clay modeling to firing the finished piece, to making plaster models, to carving finished pieces in marble. Right now, the studio is littered with pieces he is preparing for his solo show, scheduled for next September, 2022. The show will be a mixture of narrative, figure pieces and portraiture. In the show, each figure will be shown with a poem, also written by Jason.

For images of works-in-progress such as these, check out Jason’s Instagram feed.

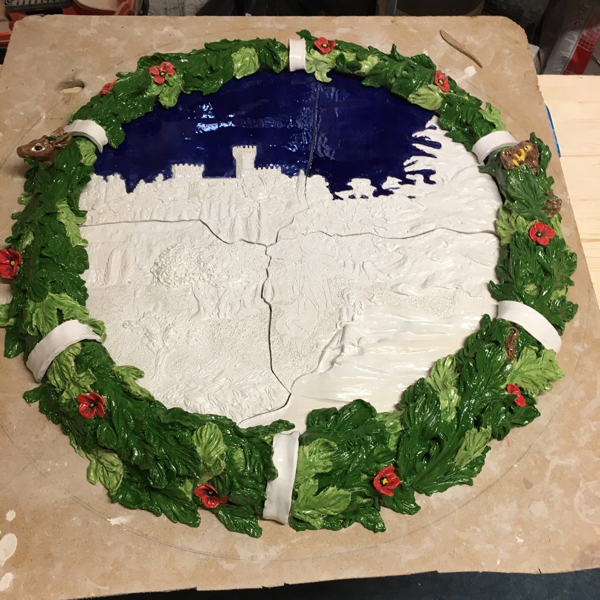

Jason also continues to work on commissions. Here’s one of his current ones for a medallion in glazed ceramic for a private residence.

The workshops I’ve been taking with him has been a good experiences. A real treat, honestly. Just to work with a live model again after 2 years (since the Florence Academy) has been great. Bodies are beautiful. What can I say. The workshop was just me, the model Chiara, and Jason. Another sculptor was also working on a personal project in one of the rooms, and he would join us for afternoon tea for our mid-session break. It was honestly really pleasant. (Except for the part where I want to tear out my hair because human figure clay modeling is challenging and frustrating, but we’ll talk about that in a different post.) Here’s Jason’s demonstration for the workshop.

The story of Jason’s life is a good example of how persistence and creativity can put a person in the right place at the right time for serendipitous events.

Yeah, no joke. And being willing to be ALL IN.